Saitama Prefecture

09. Fukaya

Party Town

Fukaya was one of the largest stations on the Nakasendo and a popular place to spend the night for travelers for its abundant inns, sake breweries and brothels. In contrast, its neighbor Kumagaya was widely known to be extremely conservative, outlawing both prostitution and alcohol in its inns. Like Itabashi, Fukaya was famous for its nightlife. It is also known for its excellent local sake and agricultural specialties grown from the rich, soft soil of the area and used for Fukaya's famous pickles. The post town was so alluring that there is still a spot on the outside of the town where lovelorn travelers heading towards Edo would look back longingly, thinking about their temporary companions, not knowing when or if they would ever meet again, before embarking on the last sections of the road into Edo.

Fukaya is also home to Shibusawa Eichi, widely regarded as the father of the modern Japanese economy. A son of a wealthy farming family, Shibusawa founded a brickmaking business in Fukaya shortly after the fall of the Tokugawa Shogunate, supplying brick for a multitude of Meiji Era buildings in Tokyo, including Tokyo Station. Fukaya Station, the local train station, is modeled after the iconic Tokyo Station buidling. He parlayed that into a business empire spanning silk production, banking and several other industries that supported Japan's transition into a modern economy. In July of 2024, his portrait will grace Japan's newly issued 10,000 yen notes. Shibusawa's ancestral home and a museum dedicated to his acheivements are both located in Fukaya.

Today, the route off and paralell to the busy Highway 17 possesses scattered period buildings, rice shops and sake breweries still operating from the Edo and Meiji Periods, some of them being repurposed into small busineses by young residents seekiing to recapture some of Fukaya's historical spirit of fun and hospitality.

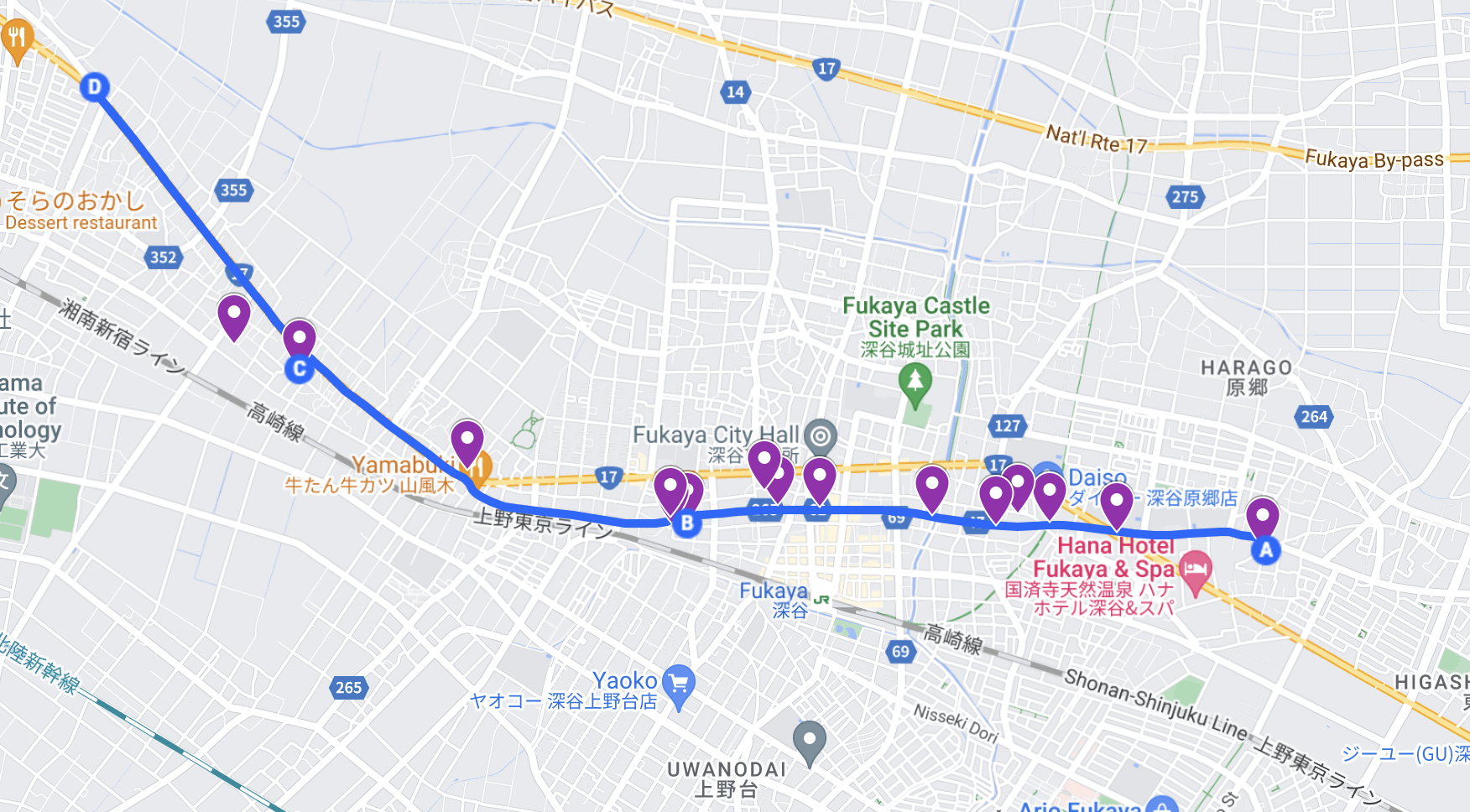

Walking Route

During the Edo Era, the entrance to Fukaya Station must have been classically dramatic. Japanese pine trees lined the road, currently most have been replaced by Gingko trees, making it equally dramatic in mid-November. The walk is all flat, and after taking the LEFT fork in the road, you pass a stone lantern marking the entrance (the matching pair is at the opposite end of town marking the exit), an Edo Era rice shop, cross a small canal, before finding yourself in the heart of Fukaya Station and its 3 sake breweries. This area deserves a bit of time.

The first sake brewery has a few original buildings in the back, is run by the same family since early Meiji. They are so friendly and proud of their excellent product. Their sake is current brewed in neighboring Gunma Prefecture with a sales shop here in Fukaya on the original property. The second, Nana Tsu Ume, is no longer a brewery, but has been taken over by a group of local artisans, with a coffee roastery, used book stores, a fortune teller, and several antique and craft shops. It is movie-set beautiful with exposed brick and ivy covered earthen walls. The third is less accessible, but is still an operating sake brewery. The property is expansive and the sake is excellent. All three properties have smokestack made from renga , brick from one of Shibusawa Eichi’s first businesses, characteristic of the area.

Also nestled in before Nana tsu Ume is the beautiful Fukaya Honjin. The hours are irregular because it is owned by one of the original families who ran the inn, playground equipment and dog houses dot the garden, but the building is beautifully maintained with several wonderful relics. After leaving the town through a masu gata corner (stone lantern #2), you enter farmland with daikon and onion fields on both sides, Okabe Clan tombs are scattered in the local temples and shrines, an Edo Era pickle manufacturer still stands, with its pickle tubs discarded down a narrow road. Continue straight to Honjo.

Points of Interest

Namiki Isshin (並木一心霊場)

Row of trees leading into the post station. rows of cedar, ginko and zelkelva trees were common features on the road providing a dramatic entrance into the post town. This row used to be cedar and matsu, now some matsu and mostly ginko remain. The lines of trees were a visual marker for tired travelers, signalling from afar that a major post town was ahead where a meal, hot bath and rest were waiting.

Mikaeri no Matsu (見返り の 松)

The next station from Fukaya leading into Edo, Kumagaya, was a sharp contrast to the fun-loving Fukaya and widely known to be extremely conservative, forbidding prostitution or inns serving alcohol. This tree is where samurai retainers travelling on the sankin kotai would whistfully look back for a last look before heading towards Edo, to say a silent goodbye to their lovers. This matsu tree is over 325 years old, witness to many a tearful departure.

Fukaya Entrance Lanterns (旧深谷宿常夜燈)

Two lanterns mark the entrance and exit of Fukaya Station, and are also in the place where there was a masu gata (90 degree turns in the road, shaped like a cedar sake cup, used for defence purposes). These lanterns were kept lit all night, and were donated by followers of the Mt Fuji worshipping group. This area going forward is where the industry of brick making began in the late 1800s, providing the materials for the classic Meiji-Era style of red brick buildings like Tokyo Station. It's also where Shibusawa Eichi had his first business.

Otani House (国登録有形文化財旧大谷邸)

Beautiful late Edo, early Meiji Period building typical of the transition from pre-modern architecture. Unfortunately, it is not open to the public.

Daimasa Rice Shop (だいまさ深谷米穀)

A rice shop founded in the Edo era and still operating today under the same family. There is a huge compound behind the shop with original kuras and warehouses. The shop itself is a well preserved example of a typical post town business, with goods on display up front and living quarters for the shopkeepers family on a raised platform in the back.

Barber Ally (理容アライ)

We're not quite sure how this area got its name, but the focus here is on the replacement of an Edo Period earthenware bridge during early Meiji with a new brick structure made possible by contributions from the surrounding villages. As the main highways began to fall into disrepair after the fall of the shogunate and the new government was focused on railroad projects, it was often up to local communities to make repairs as they became necessary. Looking closely, some brick pillars remain from the bridge that was built in 1891.

Azumashiragiku Sake Brewery (藤橋藤三郎商店)

A modern sales office stands in front of the original brewery tucked away in back. Their sake is now brewed in Gunma Prefecture, but the brick chimneys and warehouses are all original remnants of one of the three breweries in the town, an unusually high number to support the needs of the numerous inns. Managed by a lovely elderly couple, the sake here is excellent quality and well worth a sample.

Fukaya Honjin (中山道深谷宿飯島本陣跡)

Transferred from the Tanaka family in the middle of the Edo era to the Takeda family. The original upper section is very well preserved, behind the Iijima printing building. While not regularly open to the public, as it remains a private residence, if you're lucky enough to walk by when it is open for viewing, you'll find an impressive collection of original artifacts from travelers on the road, including a pair of sandals worn by Princess Kazunomiya and a writing desk used by Emperor Meiji. Honjins, especially in popular towns, received many gifts from their elite guests, sometimes discreetly offered as payment by cash-strapped travelers.

Nanatsuume Sake Brewery (七ツ梅酒造跡)

A former late Edo Period sake brewery compound, it's now a collection of small shops, a coffee roastery and a small wine tasting shop. The buildings are all original and the shop owners are engaging and welcoming. Sake is no longer made here, but it is an excellent example of the efforts of communities on the road embracing their history and preserving buildings like these to repurpose them with local businesses. Very photogenic and worth a stop.

Takizawa Sake Brewery (滝澤酒造)

Takizawa Brewery is another Edo Period sake brewery and the only one in Fukaya still brewing on the premises. The original building has a retaill shop in the front and a very helpful staff. The sake is excellent.

Donryuin (呑龍院)

Fukaya Lantern (旧深谷宿 西常夜燈)

A stone lantern marking the west end of the Fukaya juku, this particular lantern is one of the largest on the Nakasendo. While lanterns like this were usually donated by businesses or artisan associations, it was erected and donated to Fukaya in 1840 by the Fujiko (富士講) sect, a religious order worshiping Mt Fuji founded after the massive and last confirmed eruption of the iconic volcano in 1707. Although repeatedly banned by the government due to its rapid growth and messianic followers, it was agressively recruiting members throughout the Edo period. Travelers were attractive targets for conversion and spreading their message across the country.

Genshoin (源勝院)

On the road towards Honjo, there are several sites with tombs from the Okabe Clan who ruled this area. Near Genshoin, there is another temple and another shrine that both look abandoned. Genshoin is still operating, is stunning in early May with its centuries old wisteria, and contains several Okabe tombs.

Takizawa Pickle Shop (滝沢漬物(株))

Fukaya became a famous pickle producing area, with the soft, porous Kanto Loam soil perfect for growing the best daikon radishes. There are several compounds of pickle manufacturers from Edo and Meiji, but it appears that Takisawa is the last remaining operating pickle manufacturer. They have a retail shop that operates irregularly, but more interesting are the discarded pickle tubs just down the road towards Genshoin.

Red painted bell tower, also showing the masu gata street pattern used for defense to create right angles and narrow entry points to slow potential invading forces moving towards Edo. While no such threat appeared during the 250 years of peace until the fall of the shogunate in 1868, these street patterns are still prominant today in many surviving post towns.

“Young people, respect your fathers and give your Emperor unswerving loyalty. Don’t look for personal profit, but seek to profit the country…”

— Shibusawa Eichi

Shibusawa Eiichi - “The Father of Japanese Capitalism”

It would be difficult to spend any time in Fukaya without seeing an image of Shibusawa Eiichi. Easily Fukaya’s most famous and revered hometown hero, he is widely credited for creating the foundations for Japan’s modern economy. As a business-minded young man from a farming family in a post station on the Nakasendo, Shibusawa found himself in the middle of a time of historic opportunity.

As a financial official under what would be the last Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the shogunate offered him a rare chance to travel outside of Japan, traveling through France, Britain and many other European countries. A keen observer of the industrial revolution taking place in the west, he was convinced that western technology and business organizations would be a model for his own country’s growth.

With the new Meiji government eager to emulate the west to compete in the global economy, Shibusawa was offered a position in the newly formed Ministry of Finance to turn his observations into policy. In this role, Shibusawa would be a catalyst for the economic development of Japan post Meiji, introducing western capitalism to the country and the key concepts of joint stock corporations and central banking and other fundamentals of western economies..

After leaving government, he founded Japan’s first modern bank, which was the vehicle he used to set up hundreds of joint stock ownership companies in a diverse collection of industries including insurance, shipping, construction and textiles. His brickmaking business in Fukaya provided the materials used in the construction of the Tokyo Railway Station, which Fukaya’s train station is modeled after. His leadership of the Tomioka Silk factory project in the 1870s with French engineers and others created a powerful and lucrative export industry for Japanese silk. It also provided opportunities for women in Gunma and surrounding prefectures for economic advancement at a level never seen before.

Shibusawa is credited with a key role in creating over 500 companies during his career, with many still listed today on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. The success of these companies generated an enormous demand for men with administrative and modern managerial expertise, which challenged the long-standing culture of advancement through patronage and personal networks.

Determined to reverse the Tokugawa’s derision of the merchant class as parasites on society and inherently immoral, Shibusawa was a passionate advocate of a harmony between a strong ethical code and business. He also believed in a strong collaborative relationship between business and government for the benefit of the country and its citizens, a core feature of Japan’s economy to this day.

Interestingly, although Shibusawa founded literally hundreds of companies, unlike many of the new crop of entrepreneurs he refused to hold a controlling share in any of them, denying himself considerable political and economic power as a potential head of a large conglomerate or “zaibatsu.” Instead, he focused on developing businesses throughout Japan, not just in Tokyo, and actively sought and recruited like-minded entrepreneurs, providing them with skills and training to drive economic growth in other areas of the country. He was involved in over 600 philanthropic efforts, founding many hospitals and universities (Including the first women’s university) as well as Japan Red Cross.

In 2019, The Japanese government announced that Shibusawa’s image would adorn the 10,000 yen note as a tribute to his role in creating Japan’s modern economy. The new notes are expected to be in circulation by mid 2024, giving even more reason for Fukaya to take pride in its native son.

Sources and Further Reading

Jansen, M., & Rozman, G. (Eds.). (1986). Japan in Transition: From Tokugawa to Meiji. Princeton University Press.

Matsumoto, K. (2017). Shibusawa Eiichi and Local Entrepreneurs in the Meiji period. Nakagaoka University.

Sagers, J. (Winter 2014). Shibusawa Eiichi and the Merger of Confucianism and Capitalism in Modern Japan. Education about Asia, Vol. 9, No. 3.