Saitama Prefecture

03. Urawa

Marshes and Eels

Urawa was an important market town from the late 1500’s through the beginning of the Showa period in the 1920’s. The 2-7 Market and Urawa's famous temples established the town’s fame until it gained even greater prominence as a Goten, a recreational spot for the Tokugawa elite, primarily to practice falconry.

Nestled between the Arakawa and Shiba rivers, the area was a focus of efforts in the Edo Period to embark on an ambitious effort to control seasonal flooding in the Kanto Plain and improve the ability to navigate the regions rivers towards Edo. A benefit of these efforts was the creation of lowland marshes and swamps which were perfect habitats for freshwater eels.

Eel harvesting became a major industry for Urawa with Kabayaki (grilled eel on a stick) as a much sought after, inexpensive snack for travelers on the road. Grilled eel remains a reknowned specialty with a plethora of specialty restaurants in Urawa, one of which has been in continuous operation since the Edo Period. After the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923, Urawa saw a large influx of intellectuals and painters relocate from Tokyo, creating a unique character to the city. It was heavily bombed twice during WW2, but continued its expansion to become part of the city of Saitama in 2001.

Today, Urawa is in sharp contrast to many of its neighbors. Approaching the town from Warabi, travelers are met with an upscale, thriving community with diverse restaurants, entertainment venues and shops befitting its current role as capitol of Saitama Prefecture and a commuter town for workers in Tokyo. Signs of history are a little harder to come by compared to other towns on the Nakasendo, but the atmosphere makes up for it.

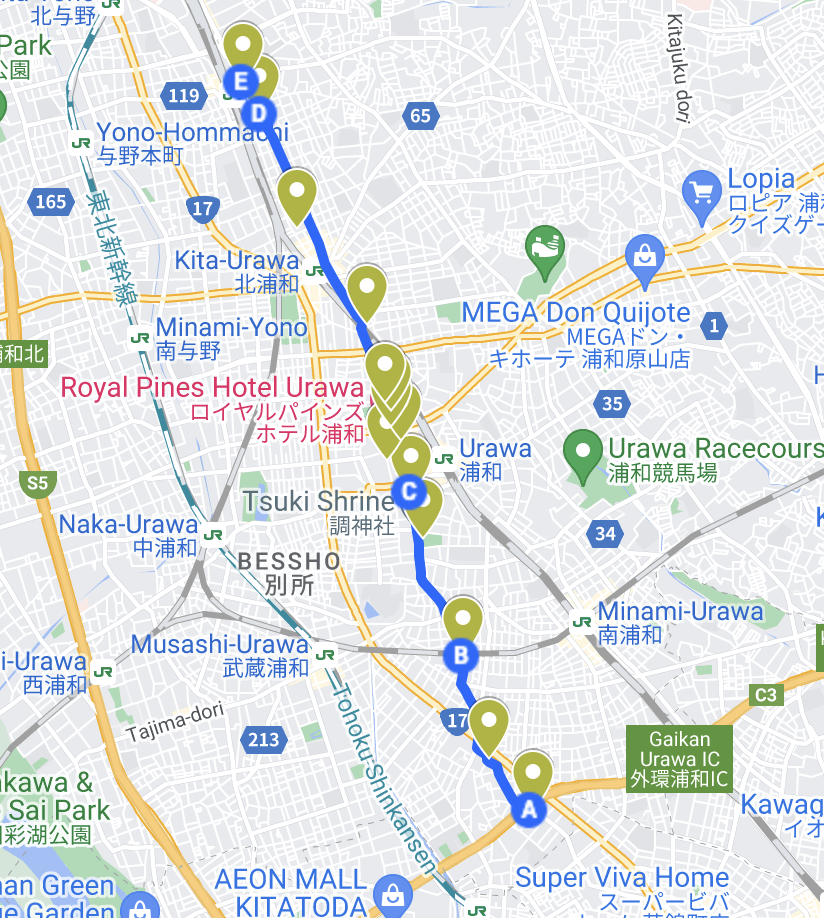

Walking Route

Crossing the Highway 17 will start the walk to Urawa. Although it crosses over one highway, and under another, the road stays primarily on suburban roads with a slight country feel. The road is two lanes with a narrow shoulder, requiring a single file walk for about a kilometer. There are a few shrines and temples along the way, but until you reach the second crossing of the Highway 17, there are no Nakasendo-related points of interest.

At the end of the first road, you’ll reach a dead end with a small park with a stream. This is the site of the Urawa Ukiyoe, where 3 roads come together, where there was once an earthen bridge and a view of Mt Asama. After this second crossing of the Highway 17, a left turn towards the town brings you to the only hill, Yaki Kome Zaka, or Roasted Rice Slope. This is another short section requiring single file walking, with curves and a narrow shoulder, but it is only a few hundred meters. Once you reach the top of the slope, you’ll see Meiji and Edo era buildings, and soon the first POI near the town, Tsuki Jinja. Continuing on the same road, you’ll go through the town and continue on to Omiya Station.

Points of Interest

Ichirizuka Milestone Marker (旧中山道 一里塚の跡

Ichirizuka Milestone with a historical marker

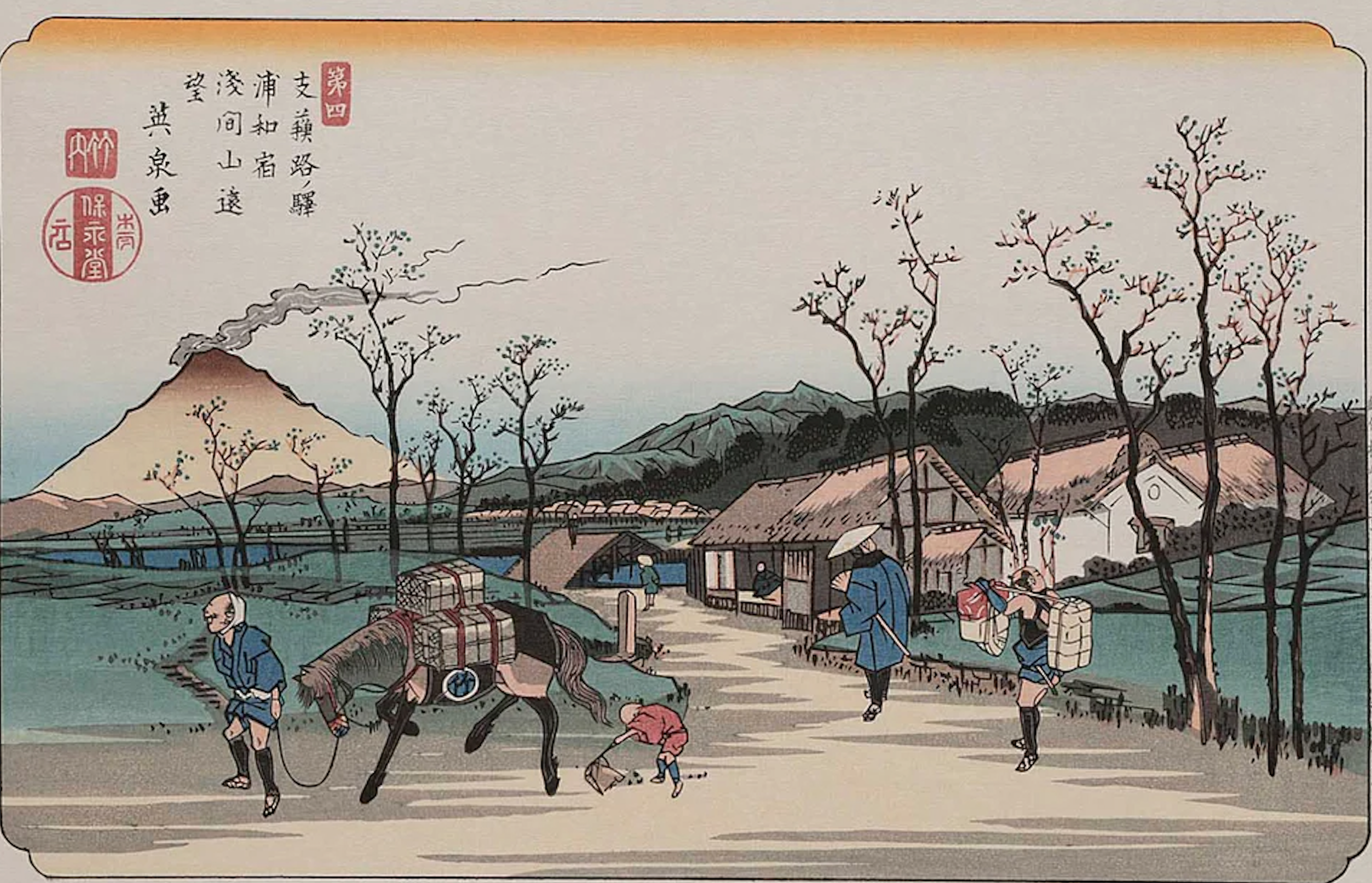

Yakigome Site (焼米坂)

On the slopes of the Arakawa river and leading up to the Omiya plateau, there was a house that would roast rice with the husks, and then remove them to eat, there was a distinctive smell, and the roasted rice is still old in this area (Yakigome) . It was perfect for travelers as it was cheap, light and could be eaten hot or preserved for later. The area was known as challenging for travelers out of Urawa towards Omiya, giving rise to a robust trade of tea houses offering grilled rice and eels for strength along the journey. In Eisen’s woodblock print depiction of Urawa, he focuses on one of these tea houses with a view of Mt. Asama in the distance.

Tsuki Shrine (調神社)

Tsuki Jinja - This pre-Heian Period shrine is situated just before the official boundary of what was Urawa station. Taxes in the form of rice harvests were collected here and dilivered to the Imperial Court in Kyoto up until the year 771. The shrine was rebuilt in 1337 and again in 1590 as a result of a fire during the Battle of Odawara during the Sengoku Period wars. in 1649, it received official recognition from Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu in the form of seven red seals which remain housed in the main hall. The shrine is extremely popular given its unusual use of rabbits as a divine messenger and symbol of good luck. It is a very famous shrine for its unusual properties.

Urawa-Shuku Marker (中山道浦和宿)

A simple marker on a busy street corner showing the beginning of the Post station.

Gyokuzoin (玉蔵院)

Founded in the Early Heian Period, it’s considered to be the most important temple in Urawa and was the center of activity in the town, along with Tsuki Shrine, long before it became a market town and post station during the Edo Period. In 1591, Tokugawa Ieyasu supported the temple prior to his elevation to Shogun. It was rebuilt after a fire in 1701 and has been gradually restored since. With numerous 100+ year old cherry trees within its grounds, it's a popular site for locals in the blooming season.

Yamazaki-ya Eel Restaurant (山崎屋)

Behind its rather sparse modern exterior lies the only remaining Unagi restaurant established during the Edo Period. Established in the early 1800s, the family who founded it had been in Urawa since the 1600s. The shop was a casualty of a massive fire in 1888 that destroyed over two thirds of Urawa. Saving only the irreplaceable sauce that is consistently added to over the course of many years, the owners operated in a temporary shop until they could rebuild again. The sauce hasn't been interrupted to this day. By the 1920's, the shop had moved on from providing kabayaki as a roadside snack to a formal restaurant with a full garden and private rooms where geisha commonly entertained guests. Famous guests included both the Emperor Akihito and his son Naruhito, the Crown Prince, who is currently the Emperor of Japan. The current iteration of this 200 year old establishment was completed in 1999. Learn more at: Yamazaki-ya

Nakamachi Park-Urawa Honjin Trace (仲町公園 浦和宿星野本陣跡)

Urawa Honjin monument - In Naka-chou park. The Hoshino family managed this Honjin. The gate to their house was moved somewhere 4 km away and is still in existence. There is a plaque about the Emperor Meiji in the park and nearby kindergarten.

2-7 Market Site (二七の市跡)

Long before the Edo Period, Urawa was chiefly known for it's famous places of worship and its markets. The site of this market (so named for taking place six times a month on the days with either a 2 or a 7 in their number) dates back to the Sengoku Period in the late 1500s and continued well into the early 20th Century. Well-known writers in the Edo Period like Jippensha Ikku, author of the classic travel comedy "Shank's Mare" often referred to the "bustle of Urawa's Inn." Even today, Urarawa has the feel of a more lively atmosphere than is neighbors.

Site of the Shrine outside the 2-7 Market Monument (二七の市跡)

This original shrine that stood in front of the 2-7 market provided spiritual protection for the merchants and customers within. Famous temples/shrines and markets were popular combinations for both locals and travelers during the Edo period, when relatively free travel was common and the roads finally safe. Urawa's possession of both and its strategic position on the Nakasendo along with being in close proximity of Edo allowed it to flourish, and become even more popular than its larger (and largely forgotten) castle town neighbor, Iwatsuki.

Sasaoaka Inari Shrine (笹岡稲荷)

Another historical site that was moved when the train overpass was built. It is unusual in that it is actually two shrines facing each other, explaing why it has 2 torii, a large and a small one. Very pretty, especially in cherry blossom season, and provides a peaceful respite from the busy road.

Kakushinji (廓信寺)

A relatively new temple, it was founded in 1609 in honor of the Iwatsuki Domain lord. It is the location of the grave of Yunosuke Kawanishi, the victim of the last officially sanctioned revenge killing in Japan. Yunosuke’s grave can be found in a small building just to the right of the main entrance. See The Ippon Sugi Incident below.

Ippon Sugi Monument (一本杉 石碑)

This inconspicuous concrete post stands next to the last cedar tree that was once a row of trees that lined the road during the Edo Period. Only this tree remained, after being struck by lightening in 1943. More interestingly, perhaps, is that it is also the site of the last Katakuichi (Sanctioned vendetta killing) performed in Japan before the practice was outlawed after the Meiji Restoration. See The Ippon Sugi Incident below.

“With the enemy who has slain his father, one should not live under the same heaven.”

— Confucian Chinese Record of Rites, Quli Section

The Ippon Sugi Incident and The Practice of Revenge Killing in Japan

On an unremarkable corner of the Nakasendo road in Saitama, in front of a pre-school in a bland, suburban section of the former Urawa juku sits a lone cedar tree with a stone marker bearing only the simple inscription of “Ippon Sugi” (One Cedar Tree). Seemingly in the “Not much to see here, move along…” category of historical sites, this lonely, unremarkable spot marks the location of the last legally sanctioned blood revenge killing (katakiuchi) of the Edo Period.

The story begins in 1860, when Saichiro Miyamoto, a retainer with the Mito Domain and Yunosuke Kawanishi, a retainer of the Sanuki Marugame Domain were traveling on a ship sailing to Edo. The two were old friends who often practiced swordsmanship and drank together. During one practice session, a quarrel ensued between the two and Yonusuke, either by accident or in a bout of martial fervor, dealt a fatal blow to Saichiro, and upon arriving in Edo, fled and went into hiding.

Saichiro’s son, Kataro, applied for and received a license from the Mito Domain to avenge his father’s death, and thus granted, set off on a search for his target that would last over 4 years. Eventually, Kataro learned Yunosuke was living in a house on this spot on the Nakasendo. On the morning of January 28, 1864, Kataro, with his two brothers and his uncle, Saichiro’s younger brother, lay in wait for their target to appear and when he did, burst through the house’s outer gate and cut him down. One account of the incident suggests that, arriving in Edo following their fateful voyage, Yunosuke, overwhelmed with remorse over the death of his friend, reportedly sought to become a monk to atone for his actions. When faced with Saichiro’s avengers 4 years later, this account describes, Yunosuke did not resist his attackers but succumbed to them. Following the attack, the four then reported to the heads of Harigaya village, within the Urawa-Juku, who interrogated them. The Mito Domain residence verified Kataro’s katakiuchi license in Edo and they escorted the four attackers back home, their 4-year mission completed with no further consequences. Yunosuke was buried on the grounds of Kakushinji Temple, just one kilometer south of the Ippon Sugi marker on the Nakasendo. The Meiji government banned the practice of katakiuchi in 1873, making Kataro’s revenge killing the last sanctioned blood revenge in the Tokugawa Period.

The Codification of Vengeance in Tokugawa Japan

The concept of revenge killing had long been established in Japan but increased dramatically during the Edo Period. Many samurai, now idle, and with no wars to fight, viewed katakiuchi as a path to honor that was no longer possible on the battlefield. The shogunate had prohibited the pursuit of most “private quarrels,” as they defined katakiuchi in 1683, and had extended that prohibition to the samurai. However, the conditional, official sanction of some forms of katakiuchi supplied a loophole for satisfying the older spirit of self-redress while staying within the official bounds of the recognized social order.

Blood revenge was a practice that was, in fact, approved, if not encouraged, by the Tokugawa shogunate, which allowed government agencies at various levels to allow vendettas. Of the sanctioned vendettas that have come down to us in the records, virtually all were undertaken by people on behalf of their relatives-for example, as in Miyamoto Kataro’s case, the revenge of a son against the murderer of his father.

The authorities vetted circumstances of a vendetta along strict guidelines. A license for katakiuchi, for example, would not be granted if the accused was apprehended by authorities and already under the jurisdiction of shogunate justice. The act of revenge was a onetime event. Retribution could not extend to other family members or clans of the accused to avoid prolonged blood feuds that would upset social order. If the target of the vendetta had died before the avenger could do the job himself, the katakiuchi license was not transferrable to other members of the target’s family. High-ranking targets of a blood revenge could offer a hereditary servant as a surrogate for the revenge target. As one observer put it, “This could be a costly strategy, but it had the advantage of preventing a feud that could last for generations.” Unlike many other privileges granted to the warrior class, the practice extended to commoners, but was most often performed by samurai.

The government took seriously the procedures in obtaining a katakiuchi license to preserve the honorable nature of the vendetta and successful applicants often received both the legal and economic support of their domains. Their income continued uninterrupted during their quest, with assurances that their families and lands would be cared for until their return. Often, expenses for the vendetta would also be reimbursed by the domain. A revenge killing that was unregistered or unlicensed from the local domain or the shogunate was a dishonorable, criminal act that would lead not only to prosecution of the avenger but also have serious, potentially life-threatening consequences for his family and their position in society.

Following the successful completion of the avenger’s mission, he and his accomplices had to turn themselves over to the authorities, who would then verify his registration of katakiuchi with the relevant domain. As in the Ippon Sugi case, they released the assailants back into the custody of their home domain, having resolved their honor according to the law.

For the samurai, honorable conduct demanded a willingness to use violence against another in a show of strength while displaying a willingness to sacrifice one's own life in restoring one's honor or that of one's extended family. Honor, or conversely, shame, could reach beyond the warrior himself and even beyond his lifespan. Seeking a license for blood revenge was a serious and risky undertaking, not just because it involved taking a life. A successful katakiuchi could cause the rapid elevation of one's honor and prestige in the domain. However, a failed or unsanctioned attempt could bring a tremendous loss of honor that would reverberate across generations.

Sources and Further Reading

Atherton, D. (2013), Valences of Vengeance: The Moral Imagination of Early Modern Japanese Vendetta Fiction, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses

Berry, M.E. and Yonemoto, M. (Eds.). (2019), What Is a Family? Answers From Early Modern Japan, University of California Press, Oakland, CA.

Curtis, J.M. (2014), Drops of Blood on Fallen Snow: The Evolution of Blood-Revenge Practices in Japan, The University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Goree, R. (2020), The Culture of Travel in Edo-Period Japan, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, November 2020, pp. 1–28.

Groemer, G. (2019), Portraits of Edo and Early Modern Japan: The Shogun’s Capital in Zuihitsu Writings, 1657 - 1855, Portraits of Edo and Early Modern Japan, Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Ikegami, E. (1995), The Taming of the Samurai, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Keene, D. (1976), World Within Walls, Grove Press, Inc., New York.

Leupp, G.P. and Tao, D. (2021), The Tokugawa World, edited by Leupp, G.P., and Tao, D.,Routledge, New York

Masahide, B. (2010), The Akō Incident, 1701-1703, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 58 No. 2, pp. 149–170.

Mills, D.E. (1976), Katakuichi: The Practice of Blood-Revenge in Pre-Modern Japan, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 10 No. 4, pp. 525–542.

Stanley, A. (2007), Adultery, Punishment, and Reconciliation in Tokugawa Japan, The Society for Japanese Studies, Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 309–335.

Teele Ogamo, R. (2021), Mochizuki, Mime Journal, Vol. 27 No. 1, pp. 111–126.

Yonemoto, M. (2020), Murderous Daughters as ‘Exemplary Women’: Filial Piety, Revenge, and Heroism in Early Modern and Modern Japan, Women Warriors and National Heroes: Global Histories, Bloomsbury Collections, London, pp. 75–92.

“To Iwamaro I say this: If you’ve slimmed down in the summer, there’s one thing that works: Catch and eat eels!”

— MAN’YŌSHŪ – MYS XVI: 3853

A Taste for Eel…

One of Japan’s most popular dishes is unagi, or grilled eel. Currently, the best eel is typically served in an old restaurant, in an old building, by a kimono clad grandma with a grandpa in the back fanning coals. It is very special in its meticulous preparation and presentation, delicious and expensive. In the Edo period, however, it was a cheap roadside snack quickly grilled over coals, slathered with a master sauce that was added to each day (often for years…) and served on sticks for eating on the go. So, how did it evolve from cheap street food sold on the Nakasendo Road to one of Japan’s most elegant meals?

At the beginning of the Edo Era, one of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s priorities was to improve the lives of a population exhausted by a century and a half of war. The bar was low; basic needs of food and shelter were at the top of the list and control over the waterways north of the capitol for agricultural expansion, defense, and transport were key priorities. The new government started ambitious waterworks projects early on, constructing river diversions and canals in every area of the Kanto Plain, from the foothills in the north to downtown Edo. This resulted in creating ponds and marshes which were the ideal habitat for eel, cultivated in virtually every village along the road in present day Saitama Prefecture.

Eel was a popular source of rare protein in the Japanese diet for centuries before the Edo period but was not common and often seasoned with only salt. Their first mention in Japanese literature goes back to the Manyōshū (万葉集) collection of poems in the 8th century. By the late 18th century, both soy sauce and mirin were being produced in the Kanto region. Combined, they created the silky, salty sweet “tare” or sauce that caramelized with charcoal grilling, melding perfectly with the eel or Kabayaki. Widely believed to promote strength and stamina, Kabayaki was served on a stick, grilled roadside, about two mouthfuls big, allowing the traveler to just slide it into their mouths while walking.

As travelers on the Nakasendo streamed through Urawa-juku, kabayaki’s birthplace, the snack exploded in popularity and its reputation was carried along the highways to the rest of the country. Naturally, the fad-conscious population of Edo caught on to the trend, with eel, or unagi restaurants trying to outdo themselves in increasingly elaborate preparations. By the early 1800s, over 20 unagi restaurants were registered in Edo as the more upscale versions of the dish took hold.

Unfortunately, unagi’s popularity over the years, combined with more efficient harvesting methods and a resulting overexploitation and degradation of natural habitats, took its toll. Local eel populations have been in a rapid decline over several decades, further speeding up within the last few years with changes in ocean atmosphere changes. While efforts are underway to better regulate fisheries and develop more effective eel farming techniques, conservation measures still are challenging.

Sources and Further Reading

Kaempfer, Engelbert, and Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey. Kaempfer’s Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawai’i Press, 1999.

Kobayashi, Akira. “Edo Eel and the Start of a Summer Tradition.” www.nippon.com

Kuroki, Mari, Martien J. P. Van Oijen, and Katsumi Tsukamoto. “Eels and the Japanese: An Inseparable, Long-Standing Relationship.” In Eels and Humans, edited by Katsumi Tsukamoto and Mari Kuroki, 91–108. Humanity and the Sea. Tokyo: Springer Japan, 2014.