Saitama Prefecture

02. Warabi

Entering the Countryside

A mural depicting Princess Kazunomiya's arrival in Warabi on her way to Edo to marry the 14th Shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi in 1861.

The Arakawa River was a traveler's first encounter with the countryside outside of Edo. With the shogunal authorities banning the construction of a bridge for defense purposes, the only crossing was by ferry. Unpredictable water levels and currents sometimes made delays inevitable, contributing to Warabi's importance as both a lodging and logistical hub, in addition to catering to delayed travelers with inns and teahouses along the riverfront. In the Late Edo and Early Meiji Periods, Warabi was an important hub for the rapidly growing cotton textile industry. Warabi has embraced its Nakasendo heritage with preserved buildings in the town center, despite being an occasional bombing target in WWII. Today, Warabi is a commuter suburb of Tokyo and home to several small and medium sized factories as well as a sizable population of foreign workers from the middle East and China.

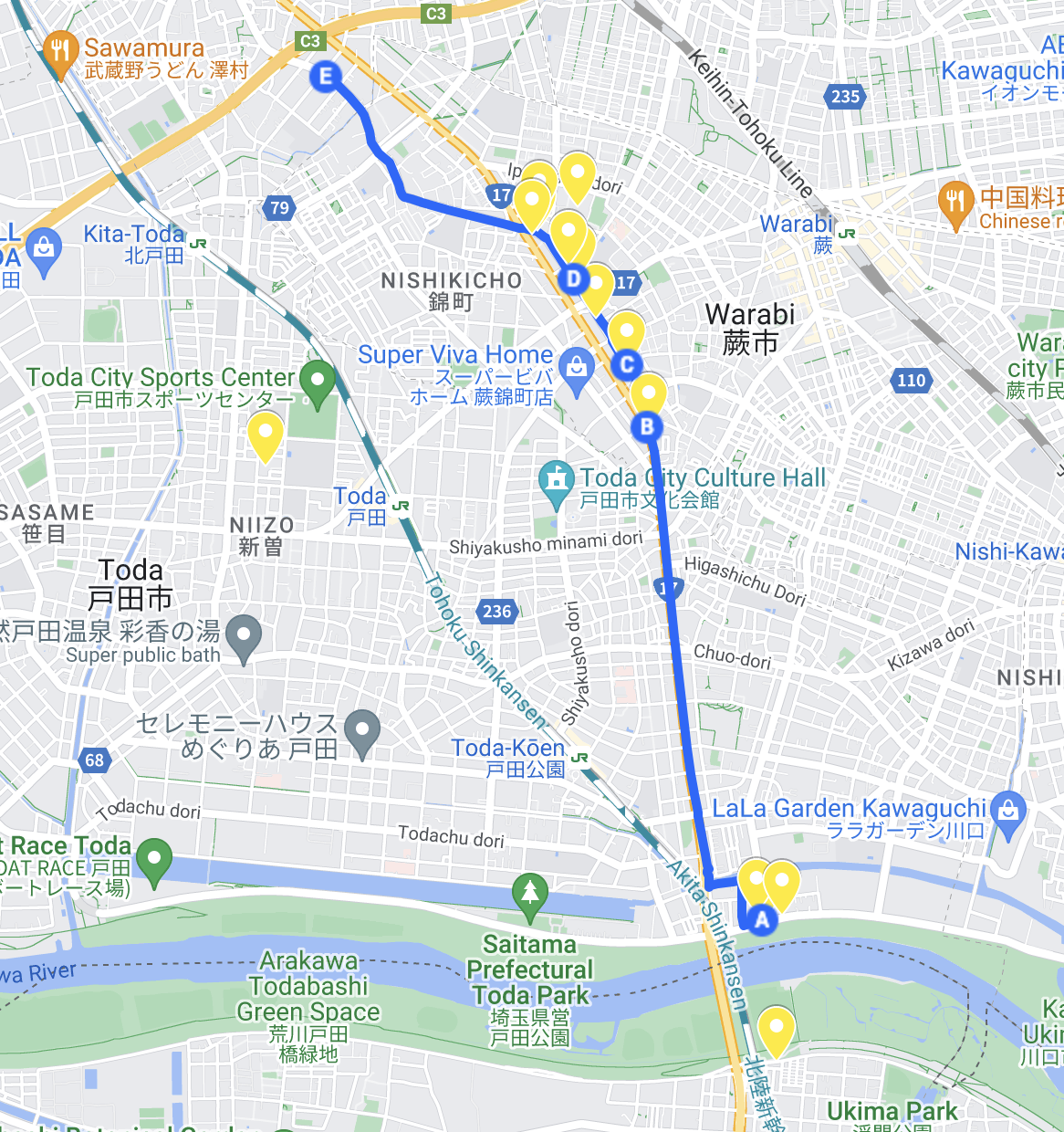

Walking Route

After the crowded streets of Tokyo, coming up the slight rise to the banks of the Arakawa River is a welcome change of scenery. After a brief walk over the busy Arakawa Bridge, the road drops down to the far bank of the river and winds through the back streets of the old Toda neighborhood, the site of Warabi's ferry port. After a 2km walk along Highway 17, the main road through Warabi, the old road veers right into a quiet neighborhood sprinkled with Edo Period buildings, old merchant houses and an excellent museum, culminating at a monument to the Nakasendo and Princess Kazunomiya's procession in 1861 (complete, for some reason, with cars, bicycles and modern cafes), before crossing Hwy 17 and following the Old Nakasendo to Urawa. The terrain, much like the rest of the next 10 stations, is flat and suburban.

Points of Interest

Arakawa Ferry Crossing Marker

The site of the river ferry crossing point on the Edo side of the Nakasendo. Bridges were often not constructed over the river due to defense concerns but also because of the inability to control flooding and currents. Part of the Tone River watershed, the Arakawa (Ara 荒 (wild, rough, rude; devastating) Kawa 川 (River)) was extremely dangerous and often flooded, changing its course in often unpredictable ways. The ferocity of rivers like the Arakawa made bridge building difficult and expensive, making the government reluctant to build (or rebuild) them. In addition, river conditions contributed to the economic growth of riverside post towns, providing inns and teahouses for travelers waiting to cross.

Mizu Shrine 水神社

The river was the key to Warabi's livelihood but also a significant risk to both the town and travelers when it flooded or became impassable. On the Saitama side of the river at the site of the actual ferry crossing in the Toda neighborhood, travelers and residents both prayed at this shrine for protection and safe passage. Its date of founding was unknown, but it became a guardian deity for people living on the river. Also housed at this shrine are the guardian deity for ships and the god of safe navigation. Locals still hold a festival for this shrine every year in mid-July. You can find an excellent model of the ferry crossing and this shrine at the Toda City Folk Museum, east of the Warabi Folk Museum.

Batokanzeon 馬頭観世音

Horsehead small shrine dedicated to the horses and animals who worked and died in service on the road. It is also enshrined as the guardian Buddha of horses in folk beliefs. In addition, it is said that it is a Kannon that saves not only horses but also all kinds of animals. Many horse-head Kannon were enshrined on the roadside where horses died suddenly, and the meaning as a memorial tower for animals became stronger.

Jizodo

Small neighborhood temple with several Edo Period jizos and grave markers. The building is considered to be the oldest wooden building in Warabi, with it's precincts dating back to the 1400s.

Toda City Folk Museum

An excellent local museum focused on the Nakasendo and Warabi's role as a river transportation hub and the early development of the eel industry. Excellent collection of traveler's items and Nakasendo-related maps and documents.

Warabi-Juku Entrance 蕨宿

After a relatively uninteresting 2km stretch on Highway 17, the old Nakasendo leaves the highway to pass through the center of the original post station. Today, the town of Warabi has devoted significant resources to embrace and preserve its heritage along the original Nakasendo, including a museum and preserved buildings from the Edo period.

Edo Merchant House Museum (Warabi Museum Annex)

A carefully preserved Edo-Period house about 250 meters before the Warabi Museum. With its garden still intact, the house is a great example of a well to do textile merchant of the period. Warabi was a thriving center of the textile industry in the region, experiencing rapid growth in the late Edo and early Meiji Periods when Japan’s opening to the West provided access to global cotton and fabric markets. Several weaving looms are available for locals to demonstrate technique from the period. Visitors are welcome to walk through the house and grounds.

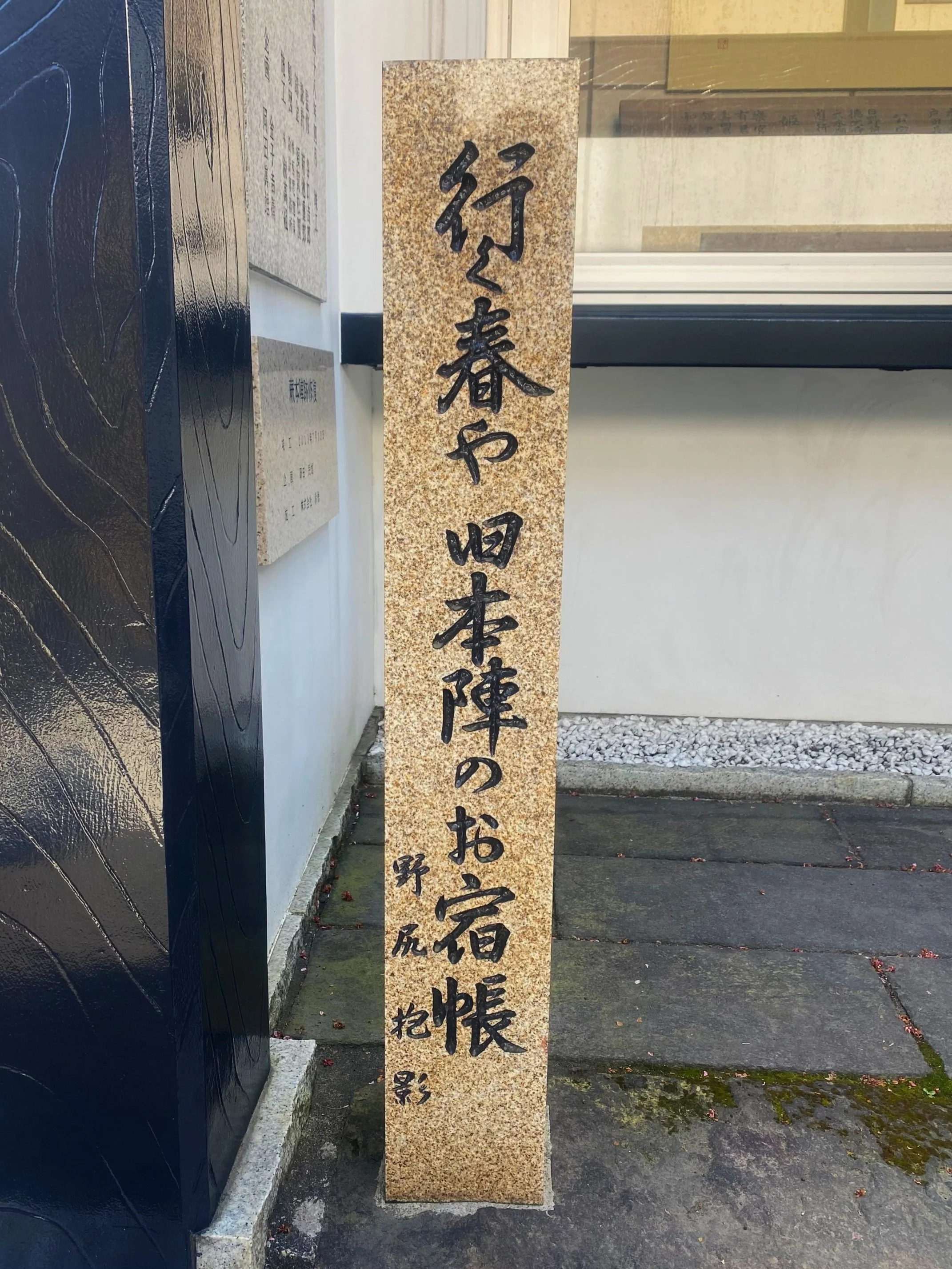

Warabi Museum and Site of the Former Honjin

A well curated museum focused almost exclusively on the Nakasendo with numerous traveler artifacts, a scale model of the post station in the Edo Period and life sized models of inns, workshops, etc. Next door to the museum, a monument to the station's Honjin, the inn where important travelers were housed. It was an inn exclusively reserved for Daimyo's and high ranking officials of the Shogunate. Princess Kazinomiya, sister to Emperor Komei stayed here on her journey from Kyoto to Edo for her marriage to Shogun Tokugawa Iemochi in an unsuccessful effort to save the shogunate in its final days. Also preserved here is an inscription carved by an unknown samurai retainer on duty under the Sankin Kotai lamenting the loneliness and struggle of the journey to Edo and being far from home (See below).

Manju Ya

A traditional sembei shop founded in the Edo Period. Sembei, a seasoned, roasted rice cracker has been a snack in Japan for centuries. However, the modern version has its origin during the Edo Period in a town located 17 km west of Warabi called Sōka. Manju Ya also sells a sembei that is a meibutsu (or, famous item) of Warabi since Edo. It was a light, tasty snack for travelers and a popular item for sale on the road.

Sangakuin

The year of its founding is unknown, but relics and other materials date to the Heian Period (794 - 1195). During the Edo Period, Tokugawa Ieyasu and subsequent Shoguns generously sponsored Sangakuin, granting it a great deal of prestige. Red Seals of the Tokugawa Shoguns are kept here as well. Formerly one of the 11 prestigious training centers for Buddhist monks in the Kanto region during the Edo Period, it’s also an important stop on several Buddhist pilgrimage circuits. It was originally on the Nakasendo itself, but was relocated off the road in successive moves to its current location. Today, it’s a beautiful and peaceful collection of temple grounds awash in cherry blossoms in spring.

Hanabashi - Textile Merchant’s House

There are several Edo Period buildings at the end of the road, including Hanabashi – a textile merchant’s house. During Edo, Warabi had many small canals around the city with one at the entrance of this house, creating something of a moat. A plank bridge was used to cross it when leaving the house. The owner of the small textile factory would bring it up at night to keep the young female workers from escaping.

Nakasendo Monument and Princess Kazunomiya Mural

A town-sponsored mural giving a pretty fanciful depiction of Princess Kazunomiya's (See below.) procession into Warabi, with a modern cafe, cars and bicycles in the background. A full map of the Nakasendo is also embedded in the sidewalk in front of the mural. While Warabi has embraced its legacy as a main post station on the road, you'll find that not all towns, particularly in modern-day Saitama, have fully invested in its past

Fire Brigade Memorial

As part of the mural and monument space at the end of Warabi, a mechanical model of an Edo Period fire brigade sits in a glass-enclosed case. Just as in Edo, fire was a frightening and common threat in post stations, particularly for travelers in crowded inns constructed from wood, straw and paper. Local fire brigades were formed in the mid 1700s to rapidly respond to this threat. They quickly gained notoriety among the public for their daring acrobatics, leaping from roof to roof to either put out blazes or tear down buildings to serve as firebreaks. A festival commemorating these firefighters is held in Tokyo each year in April, with modern day firefighters performing similar stunts.

Princess Kazunomiya

In the year 1860, Princess Kazunomiya Chikako was 14 years old and living a very privileged life in Kyoto as the sister to the sitting Emperor of Japan, Emperor Kōmei and aunt to his successor, Emperor Meiji. Emperor Kōmei had a protective instinct for his younger sister and had arranged for her engagement to a young Prince Arisugawa Taruhito years before. Her future in the royal family seemed assured, predetermined, and safe. Even at such a young age, she was a skilled poet and calligrapher. Unfortunately, the year 1860 was also a precarious moment in the Tokugawa shogunate's 250-year history, a history in which she would eventually play a pivotal role.

After over two centuries in power, the Tokugawa shogunate's control over the government was quickly fading. Opening the country to foreign powers and subsequent signing of unpopular trade agreements, dissent in the countryside over failed reforms, a stagnating bureaucracy and a growing movement to restore imperial rule had taken its toll. Influential factions within the shogunate had proposed a marriage alliance between the Emperor and the Shogun's families as the cure to the Shogunate's decline. A proposal on behalf of the 14th Shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi (also 14 years old) was delivered to Kyoto on June 3rd, 1860.

It was not well received. Kazunomiya had no desire to leave Kyoto and her intended fiancé. Emperor Kōmei, sympathetic to his sister's resistance to the marriage but aware of its significance, was also concerned with her safety because of the growing presence of foreigners in Edo and instability in the country growing. After multiple entreaties and negotiations, the imperial court finally agreed to the marriage. Kazunomiya would leave Kyoto on November 22nd, 1861.

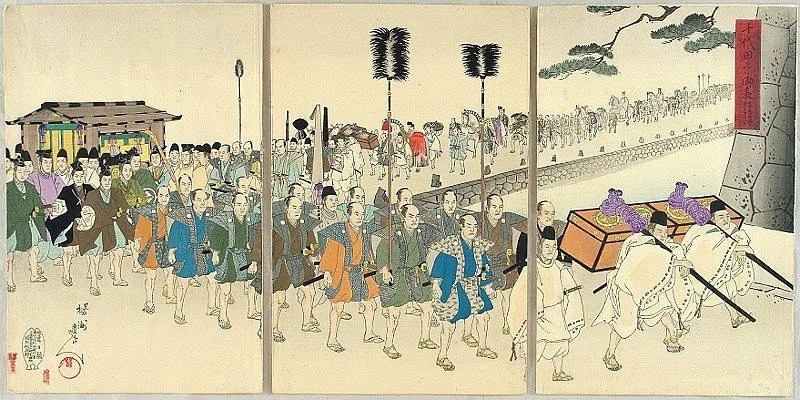

Her choice of the Nakasendo Road was not unusual for high-ranking women. Although mountainous, it had far fewer river crossings and was easier to protect than the Tokaidō. Her procession was one of the biggest the Nakasendo had seen and the shogunate had prepared the road for months beforehand, widening the road, cutting down trees, and organizing thousands of porters, horses and inns along the road to Edo. It was said that her entourage, comprising over 10,000 armed men and an equal number of attendants, retainers and personal porters, took over 3 days to pass through a post town. The journey took over 26 days, twice the time of the average traveler, and included not just sightseeing stops but detours around areas that were believed as inauspicious for the upcoming marriage.

As extravagant as it was, however, her travels on the Nakasendo are remembered to this day for her generosity to the people on the road, her kindness and ultimately what historians have perceived as her sacrifice for the good of the country at a time of great peril. All along the Nakasendo today are monuments showing where she slept, handed out dolls to children or performed other kind acts. Her reputation continued through her brief marriage to Iemochi, who apparently, she was quite fond of, committing herself to the Tokugawa family.

Ultimately, however, while the marriage did briefly achieve its goal of unifying the shogunate and the Imperial court, it did not prevent the government's eventual fall. After Iemochi's death in 1866, Kazunomiya followed tradition as a widow and took her vows as a Buddhist nun and lived quietly in Edo Castle, only increasing her reputation for selflessness and loyalty to her new family. By the spring of 1868, however, the imperial forces had surrounded Edo with two armies, one traveling east on the Nakasendo and a larger force on the Tokaidō, led, coincidentally, by Prince Taruhito, Kazunomiya's former fiancé. With Edo surrounded, the Imperial Army was intent on destroying every trace of the Tokugawa family. While representatives of both sides tried to negotiate an end to the hostilities, Kazunomiya repeatedly sent emissaries across the front lines with letters to her nephew, now Emperor Meiji and high-ranking members of the court arguing for mercy for the family and a resolution to the conflict without further casualties. While her involvement in the efforts for peace was and, it could be said, still not widely known, her entreaties were a substantial factor in the relatively peaceful fall of the shogunate without further bloodshed, paving the way to the Meiji Restoration in 1968.

After the war's end, Kazunomiya continued to live in Tokyo, at the Emperor's Meiji's request, until her death as a result of beri beri in 1877 when she was only 31 years old. She is buried at Zojō-ji Temple in Tokyo within the Tokugawa cemetery.

“Another year has come and gone and I’m back at this old inn again.”

— Anonymous Samurai inscription found at the Warabi Honjin

Advertising for tours and blogs about walking the Nakasendo try to create the image of “Walking in the Steps of the Samurai” or “Walking the Samurai Trail.” Readers often imagine a swaggering warrior bristling with swords striding on the road prepared to battle whatever danger he might come across. Images of dramatic duels and battles come to mind as part of the danger and excitement of walking the road. Most of these impressions of the Samurai come out of the Sengoku Period (1468-1598), a 130 year stretch of civil war and deadly conflict in which Samurai were indeed fierce warriors equal or superior to any fighting force in the world. After the unification of the country under the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1600, however, the role and life of the Samurai would take a dramatic turn.

Withdrawn from their defensive role in countryside fiefdoms to a more sedate life in their domain’s castle towns, the role of the Samurai assumed a decidedly less martial nature and more of one resembling corporate middle management today. The monotony of their new peacetime life was rarely broken except by a key duty of their service, going with their Domain Lord, or Daimyo, on his biennial trips to Edo and back under the Sankin Kotai (Alternate Attendance) system. With very few exceptions, all Daimyo were required to travel to and live in Edo every other year at the Shogun’s pleasure. Depending on a Daimyo’s status, these processions could number up to 2,000 retainers to protect and support him on the journey, creating a dramatic spectacle, not to mention a logistical headache, for the post stations on the Nakasendo.

Apart from serving as a security escort for the Daimyo however, Samurai did not travel in a military role, as there was simply no need. Often, their reason for travel was similar to workers in a large modern company. It was not uncommon for some samurai to avoid Edo service for several reasons that we would find relatable today. It was an arduous journey, often requiring a separation from family for many months or even years. Once in Edo, unless the retainer had specific duties to perform (And many did not), life could be boring and lonely. Often a Samurai’s only diversions were drinking, visiting the pleasure quarters in Yoshiwara and sightseeing. These activities, while initially attractive, would inevitably lose their appeal. Moreover, they were expensive. Keeping up appearances as a retainer to the Daimyo was a strain on a retainer’s stipend, particularly if they were also supporting a family back in the Domain. It was not uncommon to find Samurai selling their swords or other valuables once in Edo, with many going into debt to support their lifestyle.

Those that sought service in Edo did so for reasons also relatable to contemporary company employees. Service in the Sankin Kotai was an opportunity for career advancement in the Domain. Those with an interest in the arts, literature, poetry, or theater would find many opportunities for satisfaction in Edo. Many domains supplied travel and other subsidies for Edo service, offering a financial incentive for those retainers struggling to support their families on their existing salaries. This incentive would, however, require stringent saving while in the capitol, reducing its attraction and increasing the potential for boredom and loneliness considerably.

While the Boshin War leading to the Meiji Restoration briefly reignited the Samurai’s warrior role, this would be ended permanently with the installation of the new imperial government. Perhaps ironically, many former samurai transitioned to roles in business, creating and building iconic companies that survive in Japan today.

The True Life of a Samurai

Lee, E. B. (1967). The Kazunomiya Marriage. Alliance Between the Court and the Bakufu. Monumenta Nipponica, 22(3), 290–304.

Shiba, K. (2012). Literary Creations on the Road: Women’s Travel Diaries in Early Modern Japan. University Press of America, Inc.

Vaporis, C. N. (2008). Tour of Duty: Samurai, Military Service in Edo, and the Culture of Early Modern Japan. University of Hawai’i Press.

Vaporis, C. N. (2000). Samurai and Merchant in Mid-Tokugawa Japan: Tani Tannai’s Record of Daily Necessities (1748 - 1754). Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 60(1), 205–227.

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Kazunomiya Imperial Princess Chikako.